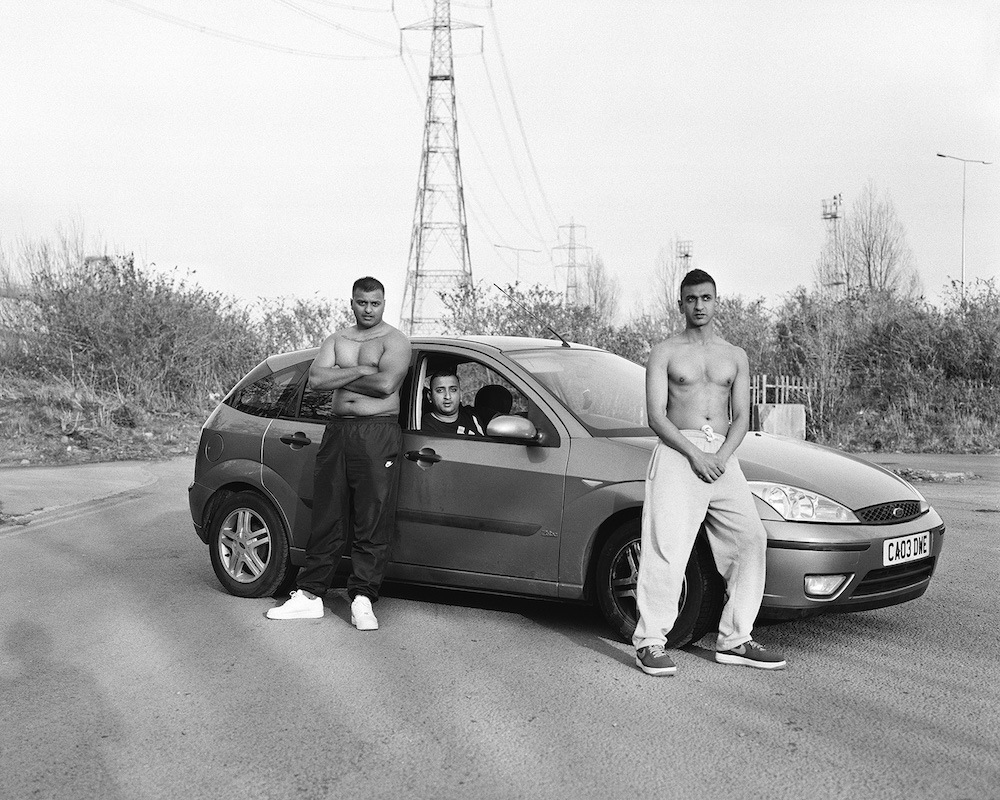

Sebastián Bruno’s series Ta-ra is the result of a decade spent living and working in Wales, a country he initially planned to visit for six months

In 2010, Sebastián Bruno arrived in Cardiff from Argentina, expecting to spend six months living and working there before travelling on elsewhere in Europe. But while in Wales he fell in love with photography, and made the country his home for more than 13 years. His latest body of work, Ta-ra – which was awarded the Mallorca Prize for Contemporary Photography 2022 and published in book form by Ediciones Anómalas in summer 2023 – represents a decade’s worth of Bruno’s photographic experiences in Wales, and provides striking insights into its people, culture, communities and collective psyche.

Aaron Schuman: How did you first get into photography, and how did you first find yourself in Wales?

Sebastián Bruno: When I was 14, I started carrying around a little camcorder – I was always filming, and wanted to study cinema. I even attempted to go to university for it in Argentina, but my head was somewhere else. Then in 2010, when I was 20, I came to Cardiff because my cousin was living here. My plan was to stay for six months, just doing odd jobs and working in restaurants, and then go somewhere else. But when I got to Wales I felt more focused and centred, and ended up staying longer than expected. After working in the UK for a year, I received a small tax refund, and used it to buy a cheap DSLR and to sign up for some photography courses at Ffotogallery in Cardiff. The person who was running the courses there encouraged me to apply to university, so I did, and in 2012 I started studying on the BA documentary photography course at the University of South Wales, Newport.

AS: That course has a long and influential history – what was your experience like there?

SB: The course, although now in Cardiff, has been renowned for 50 years, and has maintained the same ethos since its founding in 1973. This, together with a responsibility to instil in students the importance of developing work that critically engages with the world, is what keeps it relevant. Since graduating in 2015, I’ve continued my relationship with the course, and contribute by teaching, trying to pass on those same values, and the love for documentary photography that I was infected with while studying there. Everything I am, I owe to that course.

When I arrived, I already had a strong social and political consciousness – I’d always felt that I had something to say, but I didn’t know how to channel that energy and those thoughts. And I didn’t have any knowledge; I didn’t even know what ‘documentary’ was properly, I just assumed it was photojournalism or street photography. So I spent the first year trying to absorb everything. I discovered so many photographers, the projects they’d made, and the different visual languages they used.

Then, during the second year, I came to the conclusion that to be able to make work, I really needed to feel something about a subject, and to respond to place and people. At the time I was working as a waiter in a restaurant in Cardiff Bay, and I was notorious for providing either the best possible experience or the worst, depending on how much I liked the customer. It happened that the majority of the customers that I particularly disliked – and this dislike was always mutual – would frequently go to a bar upstairs, right above the restaurant. When I realised that I wanted to photograph things that made me feel something, I said to myself, “I should go and take pictures in there”. I thought that the best thing I could do would be to spend my evenings in that bar with them.

While I was doing that, I was also consuming a lot of photography made in the UK during the 1980s, which I found ideologically compatible with this project. So I started to work with one camera – a Mamiya 7 with a Vivitar 283 flash – because I wanted to borrow some of those aesthetics and find my own way around it.