© Families Suschitzky/Donat. Courtesy of Fotohof Archive

The photographer’s career has been overshadowed by her communist links and her more famous brother, but 25 years of her work is now being reappraised

Over the last decade, multiple books have appeared retracing the history of photography to include previously overlooked women. As is the way with lost histories there are many more to be foregrounded, including the story of Edith Tudor-Hart. What makes this ironic in Tudor-Hart’s case is that there are hundreds of files on her in the UK’s National Archives in Kew. But the reason those records exist is a factor in her unfair obscurity – Tudor-Hart was a committed communist and Soviet spy, and MI5 watched her for years. Other factors stymieing her progress are all too familiar from feminist histories, including the fact she had a son she had to bring up on her own, and that she experienced mental ill health.

Born Edith Suschitzky in Vienna in 1908, Tudor-Hart was the daughter of Jewish socialists who ran a left-wing bookshop and raised her in a working-class area. She trained and worked as a Montessori teacher, taking photographs in her spare time and going on to study photography at the Bauhaus in Dessau in 1928. An anti-fascist and communist, she was imprisoned for a month in 1933 for acting as a courier for the Communist Party, during which time some of her work was lost. Soon after her release she fled Austria, marrying a radical English doctor, Alex Tudor-Hart, and moving to London. She escaped the Holocaust – which killed and displaced a large part of her family – and her brother, the better known photographer and cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, also fled Europe. Their father died by suicide, and in 1937 Tudor-Hart managed to bring her mother to England.

“The portrait of her that has been painted is one-dimensional. She did very interesting work on progressive educational institutions in the 1940s and 50s, and photographed poverty in the streets”

Tudor-Hart published work with left-wing publications such as Der Kuckuck in Austria, and Lilliput and later Picture Post in the UK (both founded by Austro-Hungarian émigré Stefan Lorant). The Tudor-Harts moved in liberal circles, and in 1933 she was commissioned to photograph the Isokon, a modernist apartment block in north London. “Edith published one of the first stories on the Bauhaus in British print media, and was commissioned to photograph the Isokon’s construction over several months,” explains Stefanie Pirker, an Austrian researcher who has curated an exhibition of Tudor-Hart’s Isokon images, now on show in London. “There was a network of exiled Austrians and Germans and the Isokon became a kind of Bauhaus in Britain – a hub for an enlightened intellectual milieu.”

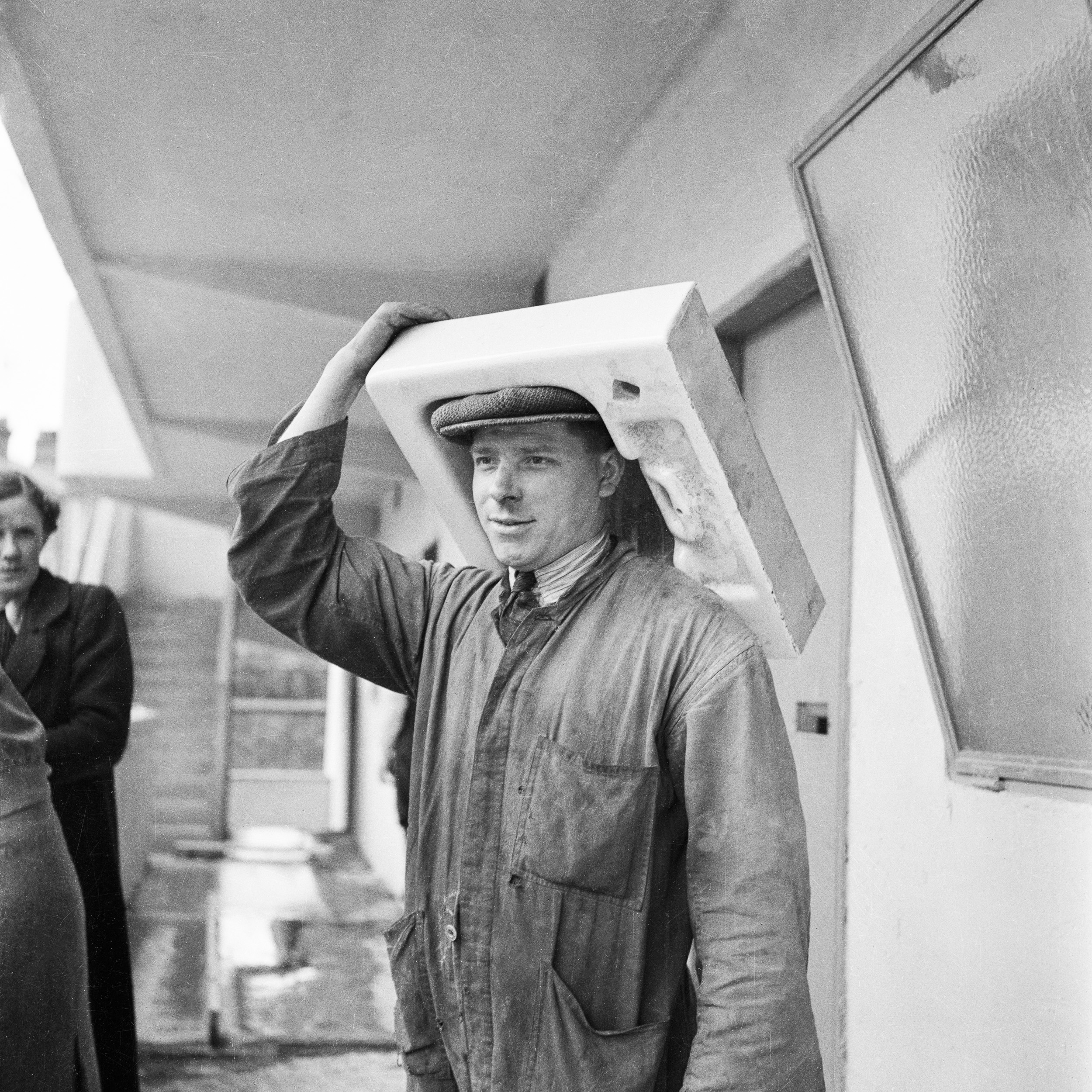

Tudor-Hart’s images from this period include shots of her friends Jack and Molly Pritchard, the couple who, along with architect Wells Coates, spearheaded the construction of the flats; she also took appealing images of Isokon’s exterior and interiors, plus its opening party. As a committed left-winger, she photographed the workmen building the flats too, acknowledging their labour and, in doing so, recording valuable information about their construction techniques. The Isokon, which is also known as Lawn Road Flats, was the first reinforced concrete apartment block in the UK, and was pitched as both technically and socially progressive. Promoting “a revolutionary way of living”, the idea was that young men and women of average means would inhabit minimally sized, but fully serviced, utopian flats.

Tudor-Hart used a balcony shot from the grand opening to make the Isokon’s first Christmas card and Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius, bought a stack to send out; he had moved in shortly after the block opened in 1934. Other residents included Marcel Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy, and (later on) Agatha Christie, while Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson were regulars at the Isobar, the building’s basement social space. Another resident was Dr Arnold Deutsch, who Tudor-Hart had known since 1926, a spy for the NKVD (Russian secret service). Other spies also lived in the flats and it is thought Tudor-Hart worked alongside them, recruiting English secret agent Kim Philby on a park bench in Regent’s Park for Deutsch’s ‘Cambridge Five’ ring.

Pirker says it is more likely she just introduced the two because she was friends with them both, but Anthony Blunt, another member of the Cambridge Five, dubbed Tudor-Hart “the grandmother of us all” in a 1964 confession to MI5. Either way, Tudor-Hart was kept under watch for years – while she and Alex lived in south Wales, where he served as a GP and she photographed deprivation in the Rhondda Valley; and after the birth of her son Tommy in 1936, and for many years after the war. Tommy was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a child (Pirker says now it would more likely be seen as a severe form of autism) and, after Alex quit the UK to help the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, the couple split up. Edith was left to look after Tommy alone.

She had to earn a living through commercial commissions, says Pirker, but she was still innovative, for example becoming one of the first UK photographers to publish images of special-needs schools. But her circumstances eventually overwhelmed her and her work, and she had what was described as a nervous breakdown in the mid-50s. It is thought she destroyed many images at that point. “From a modern perspective, it was more likely a depression,” says Pirker. “There are nearly 700 pages of files and letters in the National Archives [on her] and it’s quite sad to read them. She definitely had some misfortunes. She stopped being a photographer in the 1950s, and worked as an antique dealer in Brighton.”

According to her niece, Julia Donat, her family believed the MI5 surveillance played a large part in Tudor-Hart’s problems. “My mother claimed that Edith didn’t like her and that this was because when the police had come looking for Kim Philby and asked her whether she had any photographs of him, she had burned many of her negatives in the sink and had a subsequent mental breakdown,” Donat writes, in a publication accompanying the Isokon show. “My mother had taken her to a mental hospital.”

Tudor-Hart died in 1973 and her work has remained underacknowledged, albeit included in shows in the National Galleries of Scotland, Open Eye Gallery and, more recently, Four Corners. The full portfolio of her Isokon images might have disappeared altogether, if not for her brother. Wolfgang Suschitzky died in 2016, and in 2018 his family arranged for his archive to move to the Fotohof in Salzburg. Some of Tudor-Hart’s negatives were with this material and Pirker, a freelance researcher and member of Fotohof, came across them. Another tranche of her archive was at the National Galleries of Scotland, again acquired because of her brother, and researched by Duncan Forbes. Forbes is now director of photography at the V&A however and, the Suschitzkys having lost their champion in Scotland, this material was also moved to Fotohof Archive in Salzburg and reunited with the other part of her estate.

In Salzburg, Pirker and her colleagues have painstakingly restored and digitised this wider archive of Tudor-Hart’s images; Pirker is now completing a PhD on Tudor-Hart’s work, tracing its progress – and her life – through contemporary publications and records. Pirker also arranged for the Isokon show, which includes some 65 images, and has curated a wider retrospective opening at Fotohof in June. She plays down the espionage angle while conceding it is intriguing; the problem is it has dominated readings of Tudor-Hart’s work, she says, which was actually wide and varied.

“The portrait of her that has been painted is one-dimensional,” she says. “She did very interesting work on progressive educational institutions in the 1940s and 50s, and photographed poverty in the streets, and you can see the influence of Freikörperkultur [the ‘free body culture’ that minimised shame around nudity] in her photographs of dance. She shot on commission for companies such as Boots, and used images of her son, Tommy, to give this work authenticity. At Isokon flats she photographed the workers on breaks as well as the opening party, really bringing together everyone involved with the flats. “Her background was that of a progressive Austrian from Social Democratic circles, and you can read all that in her work,” Pirker adds. “That is exciting, and she was a fantastic photographer.”

Through a Bauhaus Lens: Edith Tudor-Hart and Isokon is on show at Isokon Gallery, London, until 26 October 2025. The accompanying book by Leyla Daybelge and Stefanie Pirker is published by Isokon Gallery Trust with Fotohof Editions. isokongallery.org fotohof.at

The post Rebuilding Edith Tudor-Hart through a feminist lens appeared first on 1854 Photography.