“It was about learning how to make something and then deciding the knowledge must stop there. With a shortage of paper I had to take whatever it was I had learned and apply it elsewhere.”

Traditionally, when Fabian Miller gets to work, he starts an image, and in the cumulative process of realising it, spots an avenue of possibilities to explore next. Projects contain projects, like nesting Russian dolls. This changed – had to change – as the threat to Cibachrome grew, and in October 2006, he began what would prove to be one of his most significant ventures: Year One, a seminal series which lasted 12 months. Each month, he investigated a single idea, knowing next month he would move on. “It was about learning how to make something and then deciding the knowledge must stop there. With a shortage of paper I had to take whatever it was I had learned and apply it elsewhere.” It resulted in a remarkable set of time-bound experiments, and he would go on to repeat the exercise once more (resulting in Year Two in 2007). “These two bodies of work represented a library of all this knowledge I had acquired, a kind of pattern book for the future. Since then, everything I have made draws from what is contained there.”

His approach shifted again in 2009, on meeting Bodkin. The pair embarked on the photographer’s first large-scale images, and the change in dimension encouraged Fabian Miller to make pictures that were unified, unbroken fields of colour. In that first year, they completed just four images, carefully figuring out how their new methods might work. “It was a dramatic shift,” he recalls, “a different way of making images, but it felt exciting.”

“Coming together with others like John [Bodkin] and the weavers has been about finding those with the same detailed commitment to colour and colour systems, but using different means of production.”

It was then too that Fabian Miller began to revisit earlier series, introducing, for instance, plants back into his exposures, knowing it would be his final chance. Blaze is unusual in that different periods of artistic enquiry are brought into dialogue with each other, and ideas that have lain dormant are given new life. Fabian Miller has also used this period to start a series of inventive collaborations with artists in other fields, to see, he suggests, “how his images might live differently in the world”. Among them are the poet Alice Oswald, a valued interlocutor who contributes an original poem to Blaze, and the cellist and composer Oliver Coates, who created a score in response to a series of his exposures, performed at the opening of the V&A’s photography centre last year. It also allowed him to build on a lifelong interest in craft, joining forces with the weavers at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh, with whom he produced a large tapestry, Voyage into the deepest, darkest blue. His practice might be on the edges, but it is solitary no more.

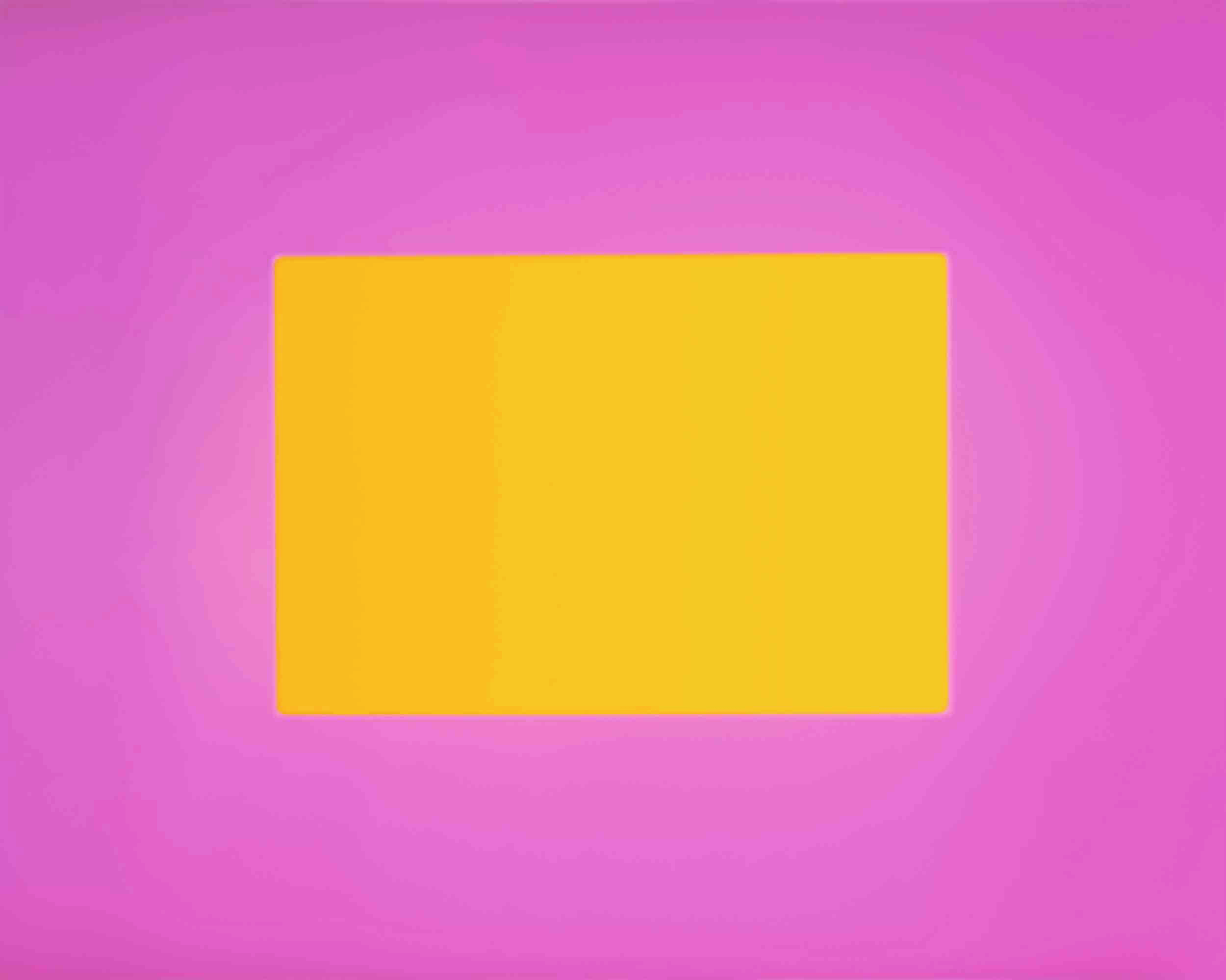

It will be on a collaborative note too, on which Fabian Miller brings his allusive body of exposures to a close. For his final series of Cibachrome exposures, he aims to produce a monument to the material’s distinct colour spectrum, to place in conversation with those in other mediums, starting with natural dye-makers, working in the tradition of the great weaver, Ethel Mairet. “Coming together with others like John [Bodkin] and the weavers has been about finding those with the same detailed commitment to colour and colour systems, but using different means of production,” he explains. With his final hundred sheets, he will realise “the last-ever Cibachrome colour palette”, in the shape of an abstract, geometric series, “like Malevich squares, icons of colour, to remember what we have lost, and what we had achieved”. After that, he will shut his darkroom, and walk home, a few hundred yards away.