While PetaPixel editor-in-chief Jaron Schneider implores drone manufacturers to make drones compelling enough to jump through regulatory hoops in the United States, law enforcement and first responders in the United States are finding plenty of reasons to fly drones. However, some critics wonder if existing limits are sufficient to curtail the questionable use of drones, especially by police.

“We’re on the cusp of an explosion in law enforcement use of drones. Is America ready?” asks Jay Stanley in a new ACLU report. Stanley is a senior policy analyst with the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project.

Per Stanley’s report, some police departments in the U.S. have gone through the arduous process of securing special Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) exceptions, allowing law enforcement to bypass the rule that drone operators must have a visual line of sight on their drones. Industry experts tell Stanley that more departments will likely receive similar exemptions in the coming months.

Police Aerial Surveillance is Rapidly Advancing

Police officers using aerial surveillance is nothing new — it is not unusual to drive down a highway in the U.S. and see a sign that police may be using airplanes to monitor motorists. However, these are typically fixed-wing aircraft which require, among other things, an actual pilot in the plane. The same goes for helicopters, which are famous participants in highly publicized police chases.

“Drones are far cheaper and can therefore be used by many more departments and in much greater numbers,” Stanley writes, adding that, “widespread police use of drones would be a major change, with implications foreseeable and not.” He also says there are good reasons to believe that a significant uptick in police drones will arrive faster than many believe.

Per Atlas of Surveillance, there are already more than 1,400 police departments in the U.S. using drones. It is important to note that not all 1,400 departments have received FAA exemption to fly drones outside the operator’s line of sight.

What is the Problem with More Police Drones?

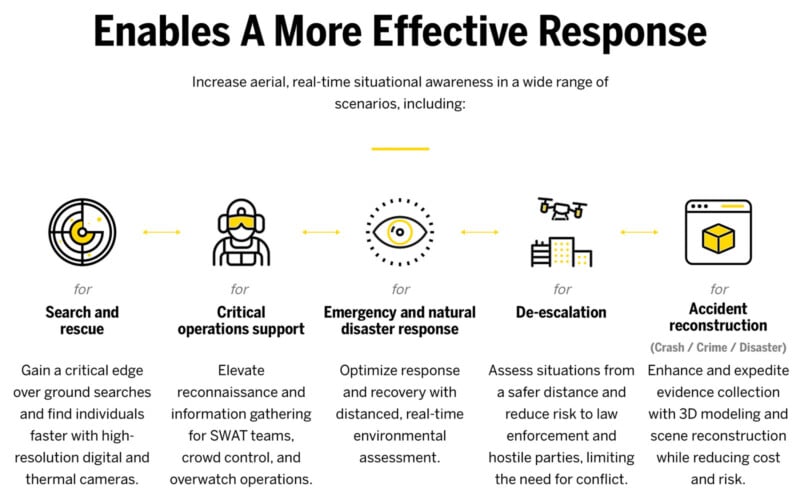

Not every case of law enforcement or first responders using drones, especially outside the line of sight, is nefarious or cause for concern. FAA exemptions allow first responders to quickly use drones to safely survey emergency scenes, in some cases before boots on the ground can reach someone who has been in an accident or is in harm’s way.

This type of emergency response is the primary motivator behind many departments applying for FAA exemption.

“The number of departments seeking such exemptions is growing. I recently spoke to Matt Sloane, the CEO of Skyfire, a consulting firm that works with public safety agencies looking to start drone programs, and he told me that ‘there’s going to be an explosion of these departments doing drone first responders (DFR) in the next six to 12 months. We’re talking to five or six departments a week,” writes Stanley.

Some companies have already begun marketing their drones as ideal for first-response tasks.

The biggest roadblock to drones being used for this purpose is the FAA’s prohibition on flying drones outside the line of sight. However, some lawmakers are actively trying to curtail regulations on “beyond visual line of sight drone flights” (BVLOS). If this type of law goes into effect, and any qualified law enforcement agent can perform BVLOS flights, this will significantly increase the number of DFR programs.

Stanley raises the concern that alongside more DFR programs, police will “push their use of drones beyond emergency response.”

There is no doubt that there are good uses for DFR programs. However, in Chula Vista, where the police department has operated a DFR program for two years, Stanley writes that “a large portion” of the department’s 14,000 drone flights are for “much less serious incidents” than the “dramatic crimes and emergencies” that Chula Vista says its DFR program is used for.

Quite a few DFR flights have responded to family and domestic disputes, wellness checks, and mental health evaluations. More concerningly to Stanley, DFR flights have also been used in response to shoplifting and surveilling “suspicious persons.” Some of the calls drones have responded to in recent months include reports of “loud music,” a “water leak,” and a person “bouncing a ball against a garage.”

The High-Value Scenarios Police Cite Are Not Always How Drones Are Used

“Police departments like to share examples of daring and excitement: drones assisting officers in tracking down suspects, providing situational awareness during tense arrests, or helping to secure crime scenes. But drill down and ask about the real case for drones, and they’ll talk about the practical matter of clearing 911 calls,” writes Patrick Sisson in Technology Review.

“This is a classic case of government powers being justified by the most serious applications and then their uses rapidly expanding to much more mundane purposes,” Stanley argues while acknowledging that to its credit, the Chula Vista police department has been “quite transparent” about its drone program. The department gave Stanley a tour of its drone operation in May, and his impression is that the department is open about its drone operation and sincerely believes that it is acting in the community’s best interest.

One way that drones, even when responding to incidents outside of the typical “first responder” emergencies, help the community is by reducing the number of potentially dangerous police interactions. Dangerous in this case refers to risk to both officers and civilians alike.

Stanley also believes the Chula Vista police department when it says that it does not intend to use its drones for general surveillance.

The Concerns Go Beyond Chula Vista

Chula Vista seems to be behaving fine with its drones, or at the very least has good intentions and is relatively transparent. However, Stanley believes there is a slippery slope concerning drone police programs.

He believes that DFR programs will quickly devolve into “drones doing everything” programs, including suspect surveillance, anticipatory monitoring based on so-called “intelligence,” patrols of “particular neighborhoods,” and routine patrolling of entire cities.

Stanley argues that the most troubling of these potential usage scenarios for police drones is the final one, “that drones will usher in an era of pervasive, suspicionless, mass aerial surveillance.”

This is not groundless speculation, despite what most police departments claim. The ACLU litigated a case alongside ACLU of Maryland to prevent the Baltimore Police Department from instituting a planned city-wide aerial surveillance system that would have used piloted aircraft. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the ACLU, ruling that the BPD’s proposed program violated the Constitution.

“But it’s not clear where the courts will draw lines, and there’s a very real prospect that other, more local uses of drones become so common and routine that without strong privacy protections we end up with the functional equivalent of a mass surveillance regime in the skies. We don’t have to think current police officials are lying to understand that mission creep is a very real tendency. While controversial new police technologies are often unrolled in limited ways and accompanied by promises of best behavior, they may be overtaken by later adopters who brush aside the limits and promises of the early pioneers,” Stanley worries.

The Beverly Hills Drone Program

Chula Vista is relatively unproblematic in its use of drones. Baltimore’s plans were shot down before they could even take off. However, Stanley points out that the city of Beverly Hills is the first in the country to “begin using drones on routine patrols.”

Following a shooting in Chicago, the city passed legislation allowing police to use drones to surveil “special events.” That ordinance is not meant to allow drone use in cases that may affect First Amendment rights.

The Omaha Police Department seems less worried about that. “During protests, we also used the sUAS [drone] to document activities from a great vantage point,” the department said.

In Elizabeth, New Jersey, police similarly used drones to monitor a protest by local students. Coincidentally, or perhaps not so coincidentally, the students were protesting the level of police presence in schools.

More Police Can Cause More Anxiety

For some people, especially those in communities traditionally harassed and disproportionately monitored by police, more police do not always encourage the increased sense of safety that law enforcement advocates often promise. In fact, it is psychologically damaging.

However, some research suggests that more police reduce violent crime and death rates meaningfully. An issue is that there is often a disconnect between the results of more policing and how that policing affects the everyday lives of residents.

Will drones flying back and forth in the sky over neighborhoods make those neighborhoods safer? Maybe. Will these drones make people feel safer? It depends.

“Of course, uniformed police officers and marked police cars already circulate throughout our communities, observing what is around them. But many people feel self-conscious and uncomfortable when a police car is driving behind or near them, or when a uniformed police officer is watching them. In communities of color where residents have sharp reasons to fear dangerous interactions with law enforcement, the negative feelings evoked by a watchful police presence can be far more powerful,” Stanley explains.

“So what happens when the presence of police ‘eyes’ expands? Won’t we have these same feelings when there are police drones flying overhead — likely armed with powerful zoom lenses (as today’s DFR drones already are) that might single us out at any time and watch with great detail what we are holding, wearing, or doing?” he continues.

Stanley is also concerned that drones may misinterpret regular everyday events, like a child playing with a toy gun or people wrestling for fun.

A drone, presumably an unarmed one, responding to a possible crime scene could result in better outcomes than armed officers being the first on the scene. Consider the example of a drone spotting a child with a realistic-looking fake gun. A drone being the first to observe this situation could play out very differently than an officer being present.

AI in the Sky

Drones themselves are rapidly advancing in capabilities. However, when artificial intelligence (AI) is added to the mix, drones may be able to help build massive databases of people’s faces and their activities. There are already disturbing trends with people using remote surveillance cameras to perform sketchy surveillance, what could happen if this surveillance technology gets a powerful AI upgrade to go along with its wings?

Police departments throughout the U.S. already claim they are overworked, underfunded, and understaffed. To think that they won’t use as much technology as possible to do more policing is naïve. More and better drones are probably inevitable.

A Balancing Act

Despite the many reasons that Stanley outlines to be worried about police using drones, he admits that there are also beneficial ways for police to use drones.

Current DFR programs are pretty limited, and while there are concerns about what could occur if they are expanded, some of the current uses of drones are helpful to police and communities alike.

In the cases of true emergencies, such as accidents, fires, and acts of violence, for example, drones can help police reach people quicker and provide valuable information to officers and emergency personnel on the ground. Information can save lives.

After crimes and other incidents, drones can also be beneficial for collecting images and information. Drones can capture crime scenes in ways that a person with a traditional camera cannot.

Drones can also reasonably assist with detailed police surveillance. Unlike the vague, somewhat aimless surveillance that worries Stanley, law enforcement often performs regulated surveillance with just cause and warrants. Drones may make this type of work safer and more productive.

It is also important to consider situations that typically involve a police response. These instances, which risk escalating into a fatal interaction, may be much safer with drones.

For example, a drone can respond to a call about a suspicious individual or group, check it out from a distance, and determine that the situation is not dangerous or illegal. When police respond to these situations without helpful information, there is always the chance of violence.

Perhaps the most beneficial outcome of law enforcement and first responders using drones concerns search and rescue missions. Drones, especially when equipped with something like thermal imaging, may help locate missing and injured people. An exhaustive canvassing effort on the ground is often challenging, and drones not only see further than people in many cases, but they can also get to areas where an officer or paramedic cannot. Some drones can administer life-saving aid, too, which is incredible.

Of course, these same arguments can be made for locating fugitives, which is also a form of public service and safety.

Proposed Regulations

Stanley and the ACLU outline guidelines that may help ensure that police drones prove beneficial and not invasive. Proposed regulations include usage limits, transparency, and strict privacy rules.

Concerning transparency, images police capture with drones must be publicly available when possible. Although, like with police body cameras, which have the nasty habit of not working in situations where police are alleged to have done something illegal, rules about drone transparency and absolute transparency may only sometimes coincide.

The Complex Drone Situation Demands Thoughtful Regulation

Ultimately, drones elicit a strong response from many. The situation causes a stronger response when people cannot identify a drone operator.

There is ample room for drones to help police protect people and save lives, even if regulations are enacted to limit ways in which police can use drones to perform sketchy surveillance.

Typical citizens must abide by relatively strict rules concerning drone use. Even if regulations for police are looser, there should still be thoughtful rules informed by intelligent decision-making and careful consideration.

It is also crucial that the potential benefits of drones in the hands of law enforcement do not result in law enforcement receiving carte blanche to do whatever they want.

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.