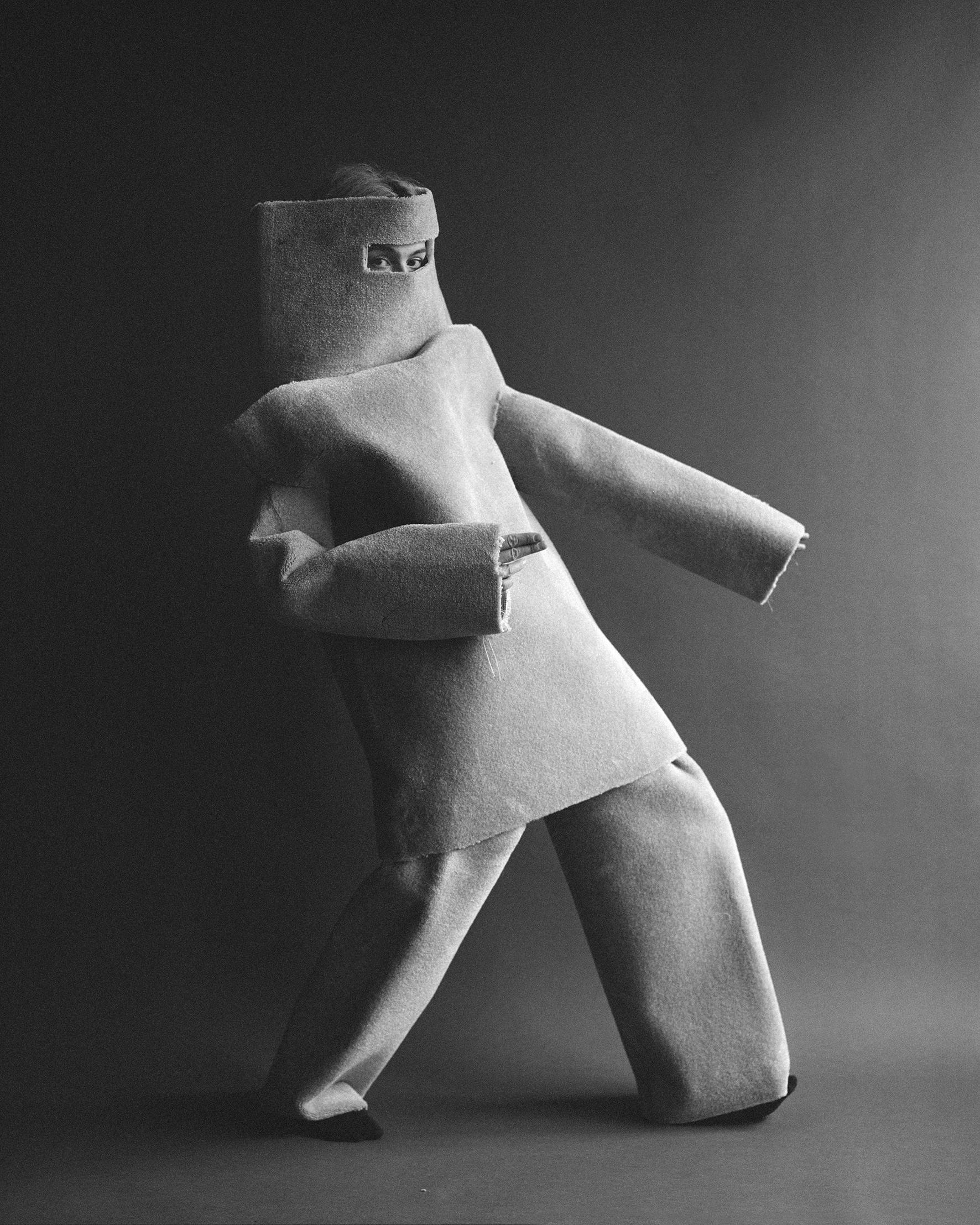

Red Whirlpool, 2023. All images © Gabby Laurent. Courtesy Flowers Gallery

The photographer explodes the traditional links between motherhood and the home with daring, often dissociative images

In 1969, shortly after the birth of her first child, the US artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote a four-page manifesto called CARE in which she reframed the maintenance work of women and mothers as art. “Working is the work,” she said in an interview with Artforum, describing her intention to reclaim her freedom while critiquing capitalism’s interdependence on domestic labour. “Our culture values development,” she reflected. But for mothers, the overlooked work of domestic labour “takes all the fucking time.”

Fast forward fifty years, and while some progress has been made, women continue to be centred in the home, juggling work and parenthood while grappling with sexism, pay disparity and childcare inequality. Like Laderman Ukeles, the work of London-based artist Gabby Laurent sits at the intersection of performance and photography, using her body as a site to explore ideas of labour, control, loss and recovery. Both artists re-centre feminist rage and agency, illustrating the value of women’s work through radical and unique visual strategies.

“Motherhood has been a wonderful thing, but it can also be a bit of a noose,” Laurent tells me from her studio in East London. “Domesticity is a place I want to be, and it annoys me that I even have to say that as a caveat, but it’s also a place of confinement – a meeting point of comfort and terror.”

Laurent explores these gendered dichotomies in Close to Home, her first solo exhibition at London’s Flowers Gallery. Through a constellation of recent projects Falling, Wearables, and new work Shrieking Wailing Sobbing, Laurent renders an unsettling encounter with domestic life that is tender and angry, playful and urgent. Girl with a Door on her Mouth is a haunting installation in which a close-up of Laurent’s screaming mouth is framed by two domestic doors, blown open by the implied force of her gesture. The work illustrates the artist’s refusal to be trapped or limited by domesticity’s physical and psychological confines. The piece also references Anne Carson’s essay The Gender of Sound, which describes how censoring women has been a vital project of the patriarchy for centuries.

The expression “close to home” suggests both safety and confrontation. Home is synonymous with comfort, yet the sentiment also carries an uncomfortable reckoning. “The home is the number one place for accidents,” Laurent explains. “Even though it’s our most familiar place – it can also be the most dangerous.” Through a playful reimagining of gesture and domestic materials, Laurent’s pictures subvert the constitution of home and motherhood and, in turn, produce a radical form of witnessing that touches on systemic social issues and Laurent’s internal struggles. And both Laderman Ukeles and Laurent use repetition as a riposte to how exploited groups are often ignored, while also highlighting how everyday life is entangled with deep inequalities.

Labour and endurance are integral to Laurent’s creative process. While there is a subtle nod to slapstick humour in Falling – where we see her ankle roll while walking down the stairs; limbs flailing; hair flung back so dramatically it feels like the protagonist’s neck could snap – what is most striking is the suffering involved in composing the images.

“The falling work was painful. The more I did it, the more I realised I had to give way to gravity to be convincing”

“The falling work was painful,” Laurent admits. “The more I did it, the more I realised I had to give way to gravity to be convincing. The fall had to be a real fall. There was a catharsis to it; a hard labour. When pain comes along [with the work], it always feels satisfying because you’re working for it.” This physical pain is also present in Wearables, in which Laurent embodies large and cumbersome costumes that are playful and aggressive in equal measure. In Wearables 2, the artist is poised for action in a costume made entirely of carpet, informed by Ned Kelly’s rudimentary armour in a painting by Sidney Nolan. “I ended up covered in carpet burns after the shoot,” Laurent explains. “The pieces are these monstrosities, held together for that second with fishing wire. Even when you’re wearing it, it’s quite constricting.”

How does Laurent feel performing for the camera? “It’s enjoyable [making the images], but I’m not thinking about how I will be perceived as the person in it,” she explains. For her, the photographs are not self-portraits. “When people talk about me being in the pictures, it’s weird because I’m always surprised I’m in them,” she explains. Her body instead becomes a “placeholder for the ideas.”

While Close to Home builds upon an intergenerational conversation about the complexity of women’s freedom, Laurent’s approach is also tuned into nuance. She seeks to unsettle and metabolise her rage while illustrating our sentience and personhood. “It’s about being a mother,” Laurent concludes. “And yet, it’s also about being a daughter and a partner. I don’t think [the work] comes from one place. It comes from all the things I am.”

Gabby Laurent, Close to Home, is at Flowers Gallery, Kingsland Road, London, until 29 April

The post Home is where the art is: Inside Gabby Laurent’s fractured domestic bliss appeared first on 1854 Photography.